Donald Trump is not, by all accounts, a great reader. But he’s memorized the Roy Cohn playbook, and in his first Cabinet meeting, on Monday, he consulted a page from it: the one on ritualized flattery.

Trump was a regular at Cohn’s summer parties, held at his Greenwich, Connecticut, estate. I covered a couple of them, and they were amazing spectacles. They attracted a whole range of movers and shakers and fixers and scoundrels, along with assorted artists and moguls: Carmine DeSapio and Meade Esposito mixed and milled with Andy Warhol and Calvin Klein. But nothing about these gatherings was more fascinating than the peculiar ritual with which they concluded, in which speaker after speaker would get up and praise the host.

Most people are lucky to hear such unending encomiums once in a lifetime. More often, they don’t hear them at all; only their children, and other assorted mourners, do. But for Cohn, it was an annual event. He would gaze out over his guests, the grizzled political bosses, lawyers, judges, businessmen, journalists, boyfriends, and other recipients of his largesse, and call on them to speak. Whether it was prearranged or spontaneous I didn’t know, but no one he selected was ever at a loss for words. Instead, each stood up, raised high his plastic cup—adorned with the same menacing caricature of Cohn that he used on his stationery, along with the letters “R.M.C.”—and sang Cohn’s praises, as Cohn, a look of bemused contentment on his face, listened raptly. The routine—in a garden festooned with flags and red, white, and blue flowers and balloons—was so astonishing to me that, having simply watched it one year, I vowed to return the next to see if it happened again, and to record it for posterity. Sure enough, it did, and with the same cast of characters. And I wrote it up for the New York Times, in the summer of 1983. My story preserved only a few flattering fragments. I’m sure there were many, many more.

The Mike Pence of the occasion, i.e. the keynoter setting the sycophantic tone, was the former Mayor of New York Abe Beame. “A fighter and a doer,” he called Cohn. Then came State Senator Roy Goodman, who described Cohn as “a very good, very close friend.” But these guys were but the warm-ups. Richard Viguerie, the direct-mail guru and publisher of Conservative Digest, described Cohn as “twenty-four karat, one of life’s great Americans.” Yet more astonishing—and not only because he was a sitting federal judge in Manhattan—was David Edelstein. As he put it, distilling the essence of Roy Cohn was like “attempting to separate the facets that make a diamond sparkle.” And topping even him was the New York lawyer Paul Windels, Jr. “If there’s one person who should be on the Court of Appeals or the Supreme Court of the United States, that person would be Roy Cohn,” he declared.

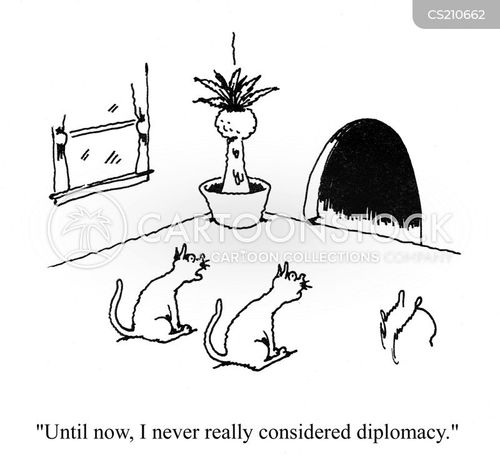

I remember looking to see if anyone suppressed a laugh as Windels said that, and no one did: it was even more unctuous than anything Reince Priebus might have managed. But, while the sentiments that night on Cohn’s estate were as slobbering as those around Donald Trump’s table yesterday, they weren’t as meretricious. The tone was entirely affectionate; no one appeared fearful, let alone to be hanging on by his fingernails. Cohn, unlike Trump, had lots of friends, on both sides of the aisle, and they clearly liked him. They detected in him a trait that’s rarely, if ever, been ascribed to Trump, a man who once saw fit to tell Chris Christie, in public, to lay off the Oreos: loyalty. One of them, Congressman John LeBoutillier, from Long Island, talked about it that night in his toast: “Loyalty,” he said, “is Roy Cohn’s middle name.” Cohn, like Trump, clearly craved all the praise, but no one offering it seemed coerced or humiliated. While Trump seems to exalt in grovelling, Cohn just needed to be loved. And Cohn guests only had to perform for a finite number of summers; think of how many more meetings Trump’s Cabinet officers must endure.

Winstonm, on 2017-June-13, 08:56, said:

Winstonm, on 2017-June-13, 08:56, said:

Help

Help